My parents come from a region in Ghana with white castles and white names that do not belong. My mother was born and raised in Anomabo and lived near Fort William, one of seventeen slave castles in the region. My father, however, is from a nearby town called Yamoransa, where I recieved my last name from my father and where my forefathers recieved our name from their masters.

White names like Sey and white castles like Fort William are shadows of Ghanaian people and Ghanaian names lost forever in the Atlantic Ocean under the Slave Trade. The legacy of slavery is immeasurable, but sometimes I wonder what Ghana would be like today if it had not participated in the Slave Trade. What if kings and tribal chiefs didn’t sell people as property to strangers? What if they didn’t trade their neighbours to Europeans for rum, mirrors, and weapons? I don’t know. But I know what Ghana is like right now.

A relatively mild disease is sometimes a death sentence. The education system is relatively good compared to other African nations. But almost half of Ghanaian parents are coerced into paying bribes to just enroll their children to school, making Ghana’s education system the third most corrupt in the entire world. The government is also notoriously corrupt to such an extent that Ghana’s current president won the election because he promised he wouldn’t be corrupt.

When I was seven years old in Ghana, war between two ethnic groups left over a thousand people dead. When I was eight years old, on my way home from school I saw two armed-robbers being burned alive by the community. I smelt their burning flesh for days. I heard their horrific screams for weeks. When I was nine years old, I was dying from malaria at a hospital right next to a cemetery. I dreamed at night that I would be buried at the cemetery the following morning. God, however, had other plans.

At ten years old in 1997, I was on a plane with my older brother. I sat in a comfortable seat. I watched movies. I ate great food. And I was safe. I was happy to leave Ghana for Canada, where my mother waited for me.

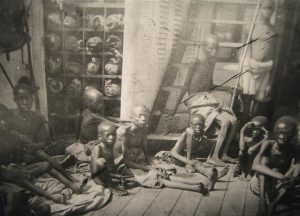

At seven years old in 1817, a girl only known as Sey with an ID number, 110923 was on a slave ship without an older brother, without a mother, without a family. She was probably one of my distant relatives and was maybe transferred from Fort William to the slave ship, where she was one of 407 slaves. She was naked, shackled to strangers, pinned to the floor and covered by feces throughout her voyage to Brazil, where her masters waited for her.

Her and I share the same name and probably the same ancestors. We may have walked on the same ground on our way to our mothers, though 200 years apart. We were alike just little children when we left Ghana for the New World. Yet, our worlds and lives couldn’t be anymore different. I flew over the Atlantic Ocean with my brother to be with my family. She struggled alone over the Atlantic Ocean to be without her family. That is the difference between 200 years. I am privileged. She was oppressed.

Black Canadians are neither slaves nor segregated. We are privileged, not oppressed. The world is not like it was 200 years ago when our ancestors jumped to their deaths into the Atlantic Ocean to avoid coming here. Now, our parents risk everything to come Canada.

Yet, we grumble that Canada is systemically racist, though we cannot name a single racist law in the nation right now. We tweet about our oppression on iPhones without guilt. We yearn for victimhood like our ancestors yearned for freedom. Are we oppressed? No. We are just so accustomed to privilege, it feels like oppression.

I, however, remember that I was delighted to fly over an ocean my ancestors never wanted to see.