Jemar Tisby’s first book does a masterful job describing how White Christians in America compromised on slavery and segregation against Black Americans. But in his attempt to expose the American Church’s supposed complicity in systemic racism today, Jemar Tisby reveals his own complicity in foolish, ignorant controversies that breed quarrels within the Church.

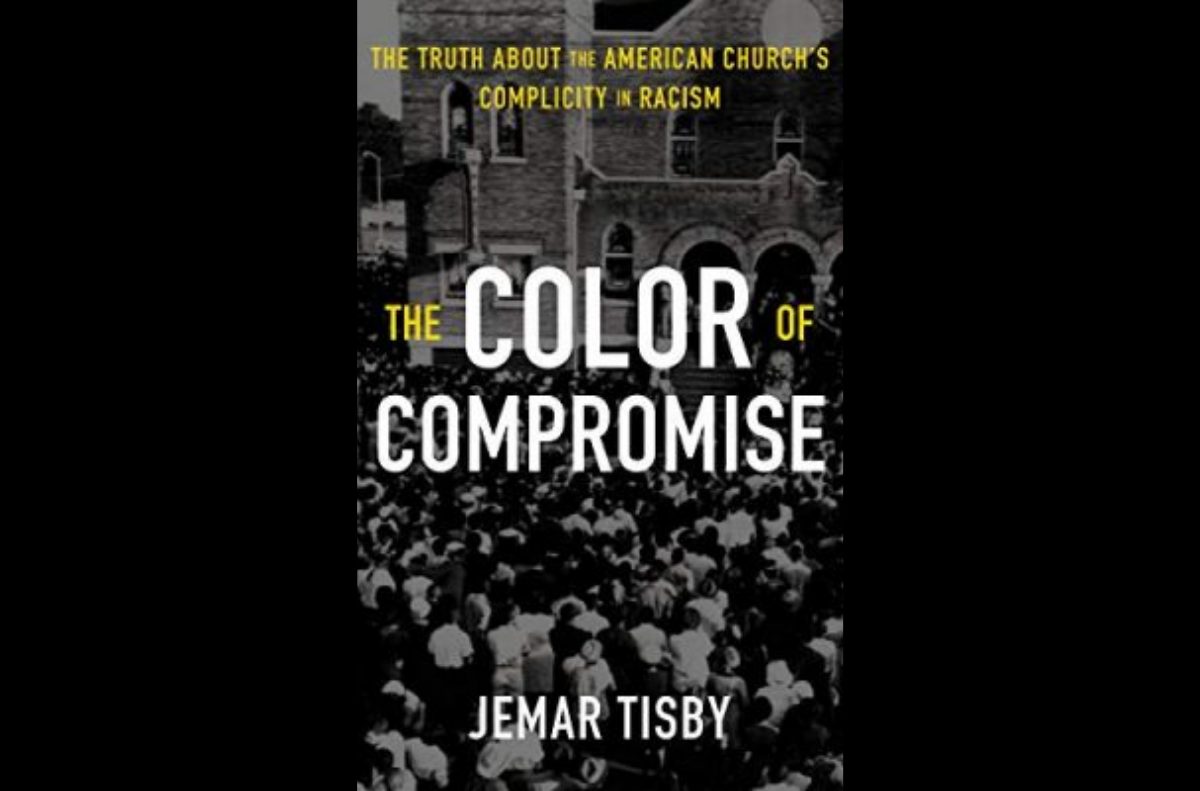

The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism outlines a history of systemic racism within the American political system and the American Church—a history of complicity in racism that Jemar Tisby argues remains to this day.

The Color of Compromise opens with the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in 1963 Alabama, when 4 members of the Ku Klux Klan planted bombs inside a Black church, killing 4 young girls and injuring 22 members of the church.

Jemar Tisby’s description of the horrific event serves as a good imagery for racism. Just as the bombing damaged the church building and its people—racism—like the bombing, has hurt many Black Americans and the American church throughout history.

That history has largely been ignored by too many White evangelicals. For instance, many Black Christians learned from their local pastors that Martin Luther King, Jr. rejected biblical Christianity, but they didn’t learn from the same pastors that evangelical heroes like George Whitefield was a notorious slave-owner who held racist beliefs about Black people.

Evangelicals have not written many books on this difficult subject, so I appreciate Tisby’s account of the American Church’s role in racism, slavery, and segregation throughout America’s history.

In the first 5 chapters of the book, Tisby details how White Christians defended slavery from 17th century Colonial America to the Civil War era in the 19th century. Tisby’s in-depth account of the American Church’s position on slavery within that time affirms that racism was the rule, not the exception within American churches.

The Color of Compromise reveals that in the 17th century, Anglicans in Virginia produced a law to ensure that slaves couldn’t be emancipated by baptism. Tisby explains that in the next century, the most prominent Christian leaders in the American church, George Whitefield and Jonathan Edwards, defended slavery and purchased slaves. Then he describes how racism produced segregation in congregations and splits within virtually every kind of protestant denomination. Tisby proves that some of the major denominations in America, including the Southern Baptist Convention, were established because of alliances between pro-slavery churches.

In Chapter 6, he explains how a Southern Baptist pastor, Thomas Dixon Jr., revitalized the Ku Klux Klan by authoring books that glorified White supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan. One of Dixon’s books was later adapted into an infamous film named The Birth of a Nation. The film is apparently America’s first blockbuster movie and became a cultural phenomenon in the early 20th century. One of the film’s biggest fans was American president Woodrow Wilson. Tisby effectively traces Woodrow Wilson’s racist beliefs to his father, a prominent Presbyterian pastor. Then Tisby shares one of the most shocking words from the entire book when he quotes a historian who estimates that 40, 000 ministers were members of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s.

If The Color of Compromise was only six chapters long, it would have been, mostly, a good book. However, at the middle of the book, Jemar Tisby approves of heretical theology from social gospel preachers and liberation theology heretics like Walter Rauschenbusch and James Cone. And when he transitions from slavery and segregation to more modern events, he shifts from irrefutable accounts to accusations and relies on perception, not proof.

The second-half of The Color of Compromise is partisan politics and leftist rhetoric masked as prophetic truth. By the 9th chapter, it becomes apparent that Jemar Tisby cannot prove that the American political system and the American Church is systemically racist against Black Americans today. And that is, perhaps, why he writes:

“At this point, readers of this book may be wondering if we will find the proverbial “smoking gun”—explicit evidence that connects the American church with overt complicity in racism. While there is no smoking gun here, we must remember that even though racism never goes away, it adapts.”

In other words, Jemar Tisby does not have evidence to back up his claims. It’s concerning that though he admits he doesn’t have “explicit” evidence for his claims, he persists in his wild accusations against millions of Americans within the Church.

When Jemar Tisby claims systemic racism has adapted into different, more covert forms of racism in our era, he immediately points to conservative politicians and conservative policies to validate his claims. He insinuates that by voting for Republicans, White evangelicals in America are complicit in racism. For that reason, much of the last section of the book reads like paid advertising from leftist groups.

At the beginning of the book, Jemar Tisby wrote: “The Color of Compromise tells the truth about racism in the American Church in order to facilitate authentic human solidarity.”

How should we facilitate authentic human solidarity? According to Tisby’s solutions at the end of the book, it isn’t the power of the gospel, but the power of “leftist” politics. His solutions for authentic human solidarity include reparations for Black Americans, removal of confederate monuments, embracing Black Theology, free education for Black students, and establishing Junteeth as a national holiday—all partisan politics and no gospel.