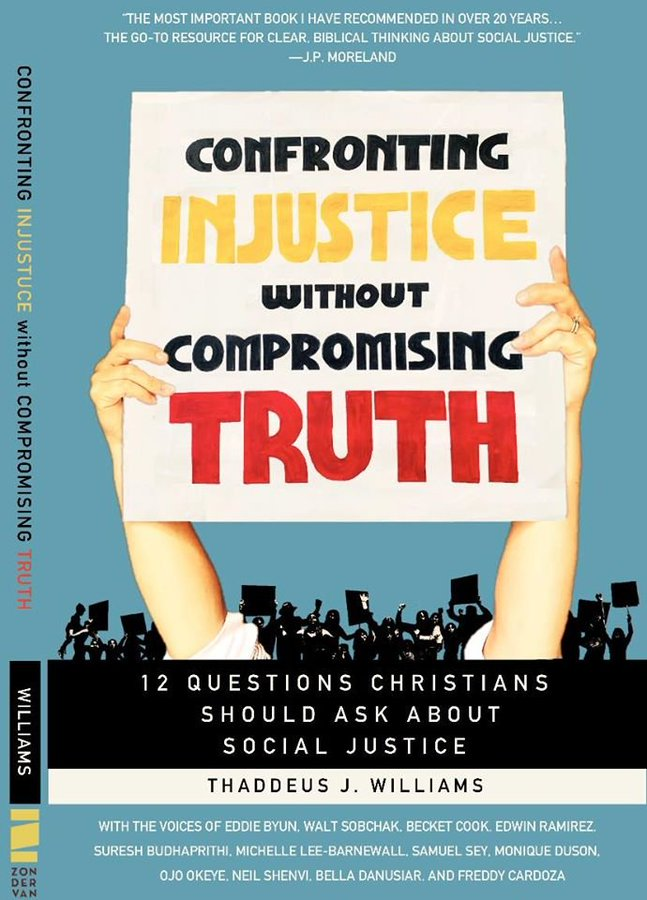

There are many great sermons, podcasts, and articles about social justice and critical theory. But there aren’t many good books about social justice and critical theory. So I’m grateful for Confronting Injustice without Compromising Truth: 12 Questions Christians Should Ask About Social Justice, a new book by author and professor Thaddeus Williams.

It’s the best Christian book on social justice and critical theory, so far. And I’m grateful I received the opportunity to write about racial disparities in the book. Here are my words from the book:

The parable of talents in Matthew 25 is one of my favorite parables.

Jesus’s story opens with a wealthy man entrusting his property to three of

his servants before leaving on a journey. The wealthy man gave “talents,”

which were large sums of money in the ancient world. He entrusted five to

the first, two to the second, and one talent to the third servant, according

to their individual abilities.

The first and second servants immediately worked hard to make a profit for their master. By the time their master returned, they had each doubled the money he had entrusted to them. The second servant didn’t receive as much money as the first. Although he also returned a 100-percent profit, he did not equal the first servant’s total profit. Despite this disparity between the first and second servant, Jesus made it clear that the master was equally pleased with them because both were faithful with what they had been given. He said, “Well done, good and faithful servant[s]. You have been faithful over a little; I will set you over much. Enter into the joy of your master” (Matt. 25:23).

But remember, there were three servants, not two. The third received one talent but failed to steward his master’s money. He didn’t even store the money in a bank to earn interest. Instead, he hid it in the ground and accused his master of exploiting others to increase his wealth. He blamed his lack of profit on his master’s character, not his own. So the master punished him and rewarded the other servants.

The master represents God, the first and second servants represent faithful Christians, and the third represents unfaithful, false converts. This parable has implications for how Christians should think about disparities, including racial disparities.

If you learned that the first and second servants where white and that the third was black, would it change your perception of the parable? What if you learned that the first servant was white and that the second and third were black? Would you think the master was racist?

Keep in mind that under this scenario, the master’s character and motives, as Jesus described, would be unchanged. The servants’ character and abilities would remain unchanged too. The only new information under this scenario would be the servants’ skin colors.

If we accept the doctrine that racial disparities are evidence of racial discrimination, then we are forced to conclude that the master was racist. Many of us embrace this kind of unhelpful thinking when we suggest racial disparities are best understood as evidence of ongoing systemic racism. But racial disparities are not—on their own—evidence of racial discrimination. Laws or policies that discriminate against people because of their skin color would indeed be evidence of ongoing systemic racism. Slavery and Jim Crow segregation were tragic cases of this. But, thankfully, such laws have been abolished in the United States.

As a black man, I understand the temptation to ascribe racial disparities to racial discrimination, especially since racism did create vast disparities between black and white Americans through history. But things have changed and, while blaming today’s disparities on ongoing systemic racism may win us the applause of the mainstream, it is no longer true or helpful.

The Bible teaches me that I shouldn’t compare my blessings with those of my (white) neighbors. It teaches me that accusing white people of racism without evidence is slander. It teaches me that if I am grateful and faithful over the little blessings God gives me, God will bless me further. It teaches me that different trees bear different fruits. Disparities are often evidence of differences, not discrimination.

God entrusts people with different blessings or privileges—because he values faithfulness, not parity. We should do the same. We’re not instructed to pursue parity. We’re instructed to pursue faithfulness and biblical justice.